12.4 Tangent Vectors and Normal Vectors

Tangent Vector and an example with graph.

Principle unit normal vector N with an example and graph.

Tangential and normal components of acceleration vector.

Proof of theorem concerning tangential and normal components of acceleration.

Example finding tangential and normal components of acceleration.

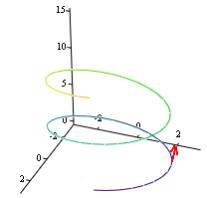

Example in R3

Example Unit tangent vector and tangent line at a point.

Since the velocity vector at time t points in the direction of motion, it must be tangent the the curve C traced by the vector valued function at time t. Hence this definition:

Def: Let C be a smooth curve traced by r(t) on an open interval I. Then the unit tangent vector T(t) at t is defined as

Ex 1 Find the unit tangent vector for the curve

traced by the vector-valued function r(t) at the point where t = p/2.

Sketch the graph and the unit tangent vector (!)

Def: Let C be a smooth curve represented by r(t) on an open interval I. If T'(t) is not 0 then the principal unit normal vector at t is defined to be

Note that the unit tangent vector points in the direction of motion at time t, and N(t) is orthogonal to T(t) and points in the direction that the object is turning. In the sketch of Ex 1 here, the principal normal vector is the purple one:

Ex 2 Find the principal unit normal vector at t = p/2

I am the first to admit this is far too ugly to do symbolically!!

Note that cos(p/2) = 0, that helps a lot!)

Go back and look at the purple vector on the graph; it appears to be correct!

Note: no exam questions will be like this!! : )

Here are two problems where a principle unit normal vector

to a vector valued function is found with reasonable detail.

For a much simpler problem look at Ex 3 pg 859 (12.4 8th edition)

Tangential and Normal Components of Acceleration

Note we showed in Unit II Lesson 2 (Ex 5) that if ||r(t)|| is a constant,

then r(t).r'(t) = 0. It's not much of a stretch to

see that if ||r'(t)|| = c then r'(t).r''(t)

= 0. In other words, if the speed is constant, then the tangent vector and

the normal vector are orthogonal. If the object has a variable speed, this

isn't necessarily so. As an example, the acceleration vector (normal) of a

projectile always points down, and would only be orthogonal to the tangent

vector when it is at its max imum height.

We do have a theorem about the acceleration vector and its relation to T and N:

Theorem 12.4 Acceleration Vector

If r(t) is the position vector for a smooth curve C and N(t) exists, then the acceleration vector a(t) lies in the plane spanned by T(t) and N(t).

Proof: T = r'/||r'||= v/||v||, so v = ||v||*T

Differentiating both sides gives

Now since a is a linear combination of T and N, it

must lie in the plane spanned by T and N. The vector a

is often represented as

Where aT is the tangential component of acceleration and aN is the normal component of acceleration. Note aT = Dt(||v||) and aN = ||v||*||T'|| for v the velocity vector and T a unit tangent vector. These can be more easily computed with the following theorem:

Theorem 12.5 Tangential and Normal Components of Acceleration

If r(t) is the position vector for a smooth curve C (that has a unit normal vector N(t)), The tangential and normal components of acceleration can be found by:

Proof: Since a lies in the plane of T and N, projTa

= (a.T)T  and projNa = (a.N)N, so we have

the middle part of the equations above. Since T = v/||v||,

we have the rest of the top.

and projNa = (a.N)N, so we have

the middle part of the equations above. Since T = v/||v||,

we have the rest of the top.

Note vxa = ||v||Tx(aTT+aNN)

= ||v||aT(TxT)+||v||aN(TxN)

Note TxT = 0 (why?) so this simplifies to ||v||aN(TxN).

Now ||vxa|| = ||(||v||aN(TxN))||

= ||v||aN.

Therefore aN = ||vxa||/||v||. To get the last part, note ||a||2 = a.a.

a.a = (aTT+aNN).(aTT+aNN) = (aT)2||T||2 + 2aTaNT.N + (aN)2||N||2

Note ||T|| = ||N|| = 1, and T.N = 0, so what we have here simplifies

to a.a = aT2 +

aN2. Solving for aN gives:

Ex 3 Find the tangential and normal components of acceleration for the vector-valued function: (without finding T and N)

r(t) = (cos(t) + t*sin(t))i + (sin(t) - t*cos(t))j

v(t) = (-sin(t) + t*cos(t) +sin(t))i + (cos(t) + t*sin(t) -cos(t))j

= t*cos(t)i + t*sin(t)j

a(t) = (-t*sin(t)+cos(t))i + (t*cos(t) + sin(t))j

aT = Dt||v|| = Dt|| (-sin(t) + t*cos(t) +sin(t))i + (cos(t) + t*sin(t) -cos(t)j||

= Dt|| t*cos(t)i + t*sin(t) j||

= Dt(sqrt(t2*cos2(t)+t2*sin2(t))

= Dt (sqrt(t2))

For aN, note a.a = (-t*sin(t)+cos(t))2 + (t*cos(t) + sin(t))2

= cos2(t) - 2t*cos(t)sin(t) + t2*sin2(t) + sin2(t) + 2t*cos(t)sin(t) + t2*cos2(t)

= t2 + 1

aN =sqrt((a.a) - 1)

= sqrt(t2 + 1 - 1)

= t

Now we can write:

a = aTT + aNN

= T +tN

Ex 4 Find T,N,aT and aN at t=0 for the space curve

r(t) = etcos(t)i + etsin(t)j + etk

v(t) = (etcos(t) - etsin(t))i + (etcos(t) + etsin(t))j + etk

v(0) = i + j + k

||v(0)|| = 1/sqrt(3)

a(t) = (etcos(t) - etsin(t) - etcos(t) - etsin(t))i + (etcos(t) - etsin(t) + etcos(t) + etsin(t))j + etk

a(t) = (- 2etsin(t) )i + (2etcos(t))j + etk

a(0) = 2j + k

T(t) = v/||v||

= ((etcos(t) - etsin(t))i + (etcos(t) + etsin(t))j + etk)/||(etcos(t) - etsin(t))i + (etcos(t) + etsin(t))j + etk||

= ((etcos(t) - etsin(t))i + (etcos(t) + etsin(t))j + etk)/(sqrt(3)et)

=(1/sqrt(3))((cos(t) - sin(t))i + (cos(t) + sin(t))j + k)

T(0) = (1/sqrt(3))(i + j + k)

N(t) = T'(t)/||T'(t)||

= (1/sqrt(3))((-cos(t) - sin(t))i + (-sin(t) + cos(t))j)/||(1/sqrt(3))((-cos(t) - sin(t))i + (-sin(t) + cos(t))j)||

= (1/sqrt(2))((-cos(t) - sin(t))i + (-sin(t) + cos(t))j)

N(0) = (1/sqrt(2))(-i + j)

so at t = 0, we have

aT = a(0).T(0) = sqrt(3)

aN = a(0).N(0) = sqrt(2)

Ex 5 Find a unit tangent vector and the parametric

form of the equation of the line tangent to the curve r(t) =

<2sin(t),2cos(t),4sin2(t)> at point P(1,sqrt(3),1)

r'(t) = <2cos(t),-2sin(t),8sin(t)cos(t)> and at P(1,sqrt(3),1), the t value of the function would be t = p/6

r'(p/6) = <sqrt(3),-1,2sqrt(3)> and T(p/6) = r'(p/6)/||r'(p/6)|| = (1/4)(<sqrt(3),-1,2sqrt(3)>).

Note we can use direction numbers sqrt(3),-1, and 2sqrt(3), so at the point P we get parametric equations x = sqrt(3)t + 1, y = -t + sqrt(3), z = 2sqrt(3)t + 1

Assignment: Read example 7 page 865, 12.4 # 3, 5, 7, 9, 15, 21, 25, 27, 39, 41, 45, 49, 55, 57, 73